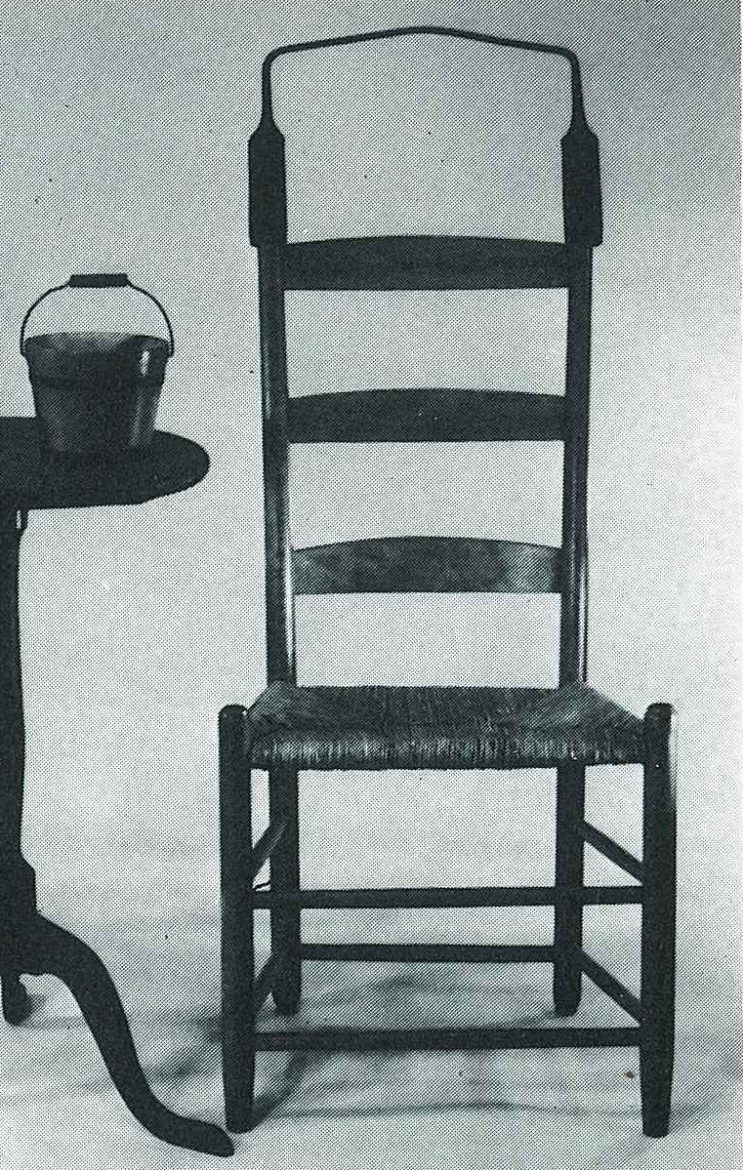

Photograph of a Side Chair, Second Family, Mount Lebanon, NY. Shaker Auction, Willis Henry Auctions, 1983, lot 48.

The Shakers showed themselves in many instances to be concerned not just with keeping all community members in union, but in creating compassionate solutions for their brothers and sisters with physical or mental disabilities to fully participate in the community and its habits and traditions.

Early Shaker brothers were forbidden from allowing their beards to grow, a rule likely meant to keep all in union and to help the constant fight against prideful thoughts. Since there would naturally be a great variety in color and the thickness of beards grown, it was thought that some judgment might be made as to who had the best beard – therefore, no beards at all. Although there was a movement to allow the brethren to grow beards in the 1850s, not until the 1870s, at least at Mount Lebanon, were they allowed to do so.

Brother Adonijah Jacobs was one of the first gathered in to New Lebanon in 1787 and was a member of the Church Family until he moved to the Center Family in 1820. At some point in his old age, he developed palsy and became unable to shave himself. The Shakers showed themselves in many instances to be concerned not just with keeping all community members in union, but in creating compassionate solutions for their brothers and sisters with physical or mental disabilities to fully participate in the community and its habits and traditions. In this way, they were early forebears of the present-day disability inclusion movement, an international effort to ensure that people living with disabilities have the same opportunities, rights, and independence as everyone else.

Elder Alonzo Harris, born in 1830, was a young boy when he came to live with the Shakers. Caring for an aged brother would have been a typical job for a responsible young Shaker and Elder Alonzo cared for Brother Adonijah. He describes that job and a unique piece of furniture that was created to accommodate Brother Adonijah in his efforts to remain clean shaven:

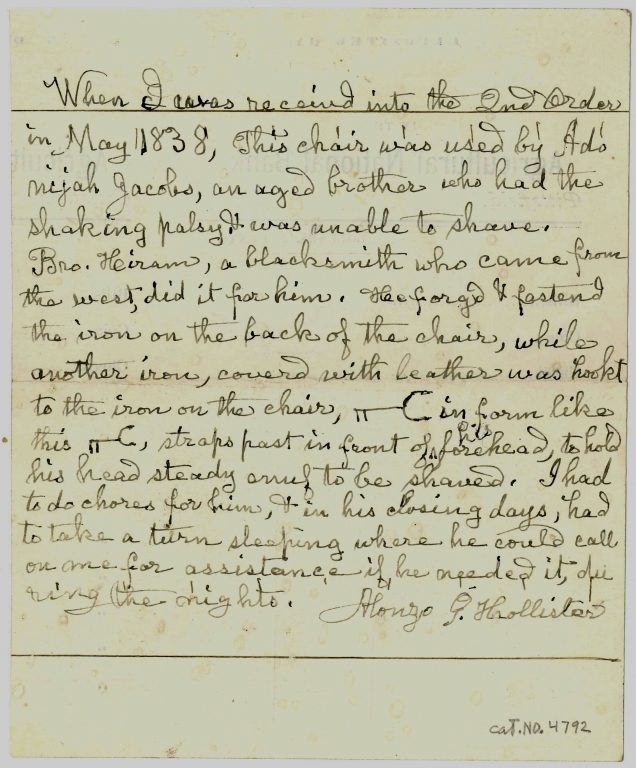

Note Written by Elder Alonzo Hollister, n. d., Center Family, Mount Lebanon, NY. Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1951.4792.1. Hollister experimented with alternative phonetic spelling systems and much of his writing include variant spellings.

When I was received into the 2nd Order in May 1838. This chair was used by Adonijah Jacobs, an aged brother who had the shaking palsy & was unable to shave. Bro. Hiram [Rude], a blacksmith who came from the west, did it for him. He forged & fastened the iron on the back of the chair, while another iron, covered with leather was hookt to the iron on the chair, [drawing of neck support] in form like this [repeat of the drawing of the neck support], straps past in front of his forehead, to hold his head steady enuf to be shaved. I had to do chores for him, & in his closing days, had to take a turn sleeping where he could call on me for assistance if he needed it, during the night. Alonzo G. Hollister.

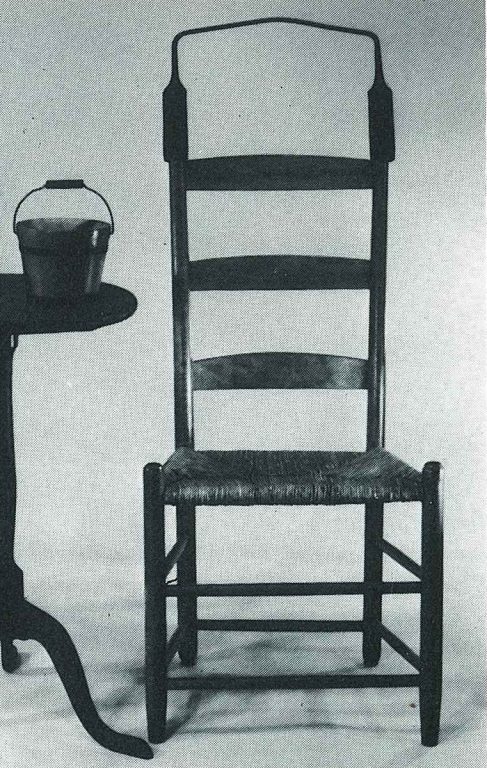

Photograph of a Side Chair, Second Family, Mount Lebanon, NY. Shaker Auction, Willis Henry Auctions, 1983, lot 48.

While the apparatus described for holding Brother Adonijah’s head has never surfaced, it is possible that the chair to which the apparatus was attached has. In an auction in 1983 a Shaker side chair was described as having an iron shawl bar between the top of the two back posts. Usually rods installed across the top of the back posts of chairs were for attaching a cushion. This made it more comfortable to sit against the wood slats of a typical chair. It makes little sense that such labor would have been put into making one out of iron – especially one, as shown in the photograph, that had elongated cups forged to fit over the finials of the chair. There are much simpler solutions to creating a cushion rail. The chair described in the auction catalogue was acquired at Mount Lebanon in 1934.

A persistent challenge in working with historical collections is locating documentation that explains or enhances the understanding of individual objects. Less often the challenge is reversed – to locate objects that are described or alluded to in historical documents. Typically documentation follows the object, but there are many intriguing pieces like this one, described in the Shakers’ records but not yet discovered. Whatever the story of the chair that sold at auction in 1983, it should be considered a good candidate to fill in a missing link in Elder Alonzo’s note, and, of course, any further information will be appreciated.