Great Stone Barn, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1948. Shaker Museum: 1998.2.5. Phelps Clawson, photographer.

Recently the Shaker Museum presented an online talk illustrating the history of the Great Stone Barn built in 1859 by the North Family Shakers at Mount Lebanon. The barn was the last in a series of very large dairy barns built by the Shakers in the 19th century. The barn included some basic tried-and-true features […]

Recently the Shaker Museum presented an online talk illustrating the history of the Great Stone Barn built in 1859 by the North Family Shakers at Mount Lebanon. The barn was the last in a series of very large dairy barns built by the Shakers in the 19th century. The barn included some basic tried-and-true features intended to make tending a large herd of milk cows easier for the Shaker brothers. It is a “bank barn,” aka a barn built into the side of a hill, making it possible to bring hay into its top floor – unloading a hay wagon by pitching hay down into the hay mow, instead of lifting it from the ground to a higher floor. This was not a uniquely innovative feature for a Shaker barn – the famous Round Stone Barn at the Hancock, Massachusetts Shaker Village, built in 1826 – and bank barns in general were found in the world outside Shaker villages. The ramp and the driveway that ran the length of the barn terminated in a space large enough to turn a team of horses or oxen around so they could be led out of the barn without backing up. While convenient, this feature was also not unique; a barn built in the 1850s by the Shirley, Massachusetts Shakers may have had a similar arrangement.

Manure Car on Railroad, Great Stone Barn, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1950s. Photographer unidentified.

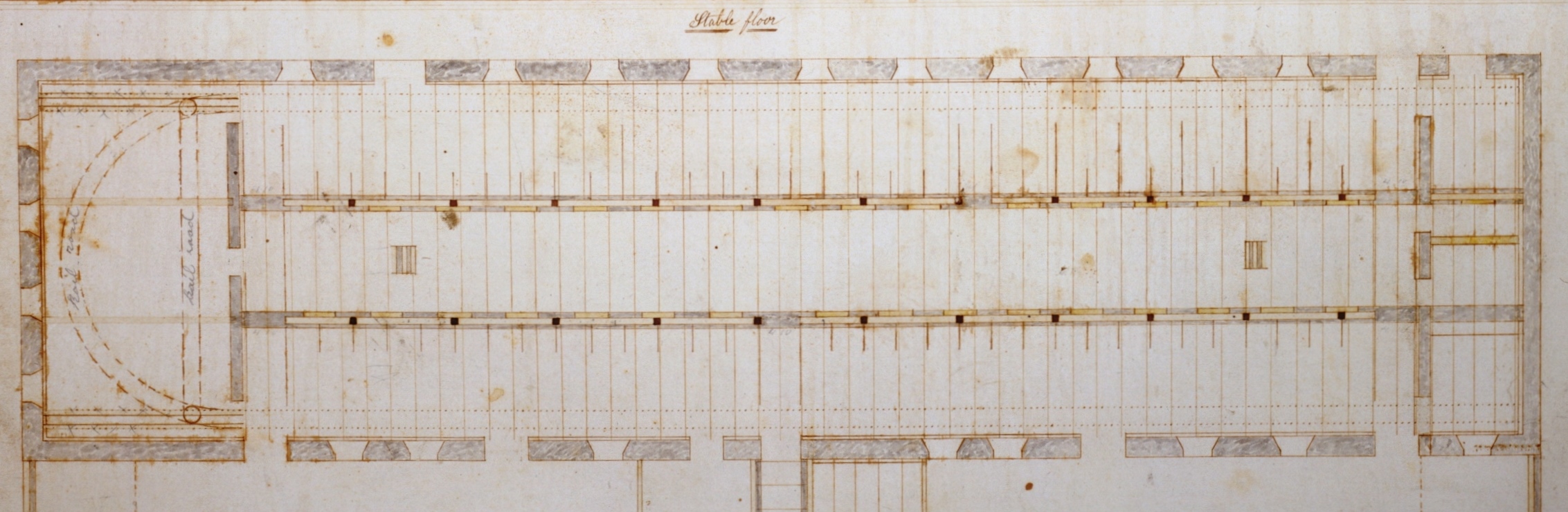

One of the innovative features in the Great Stone Barn was the manner in which manure was handled. By the time the Great Stone Barn was built it was generally accepted that manure needed to be stored out of the weather – generally in the cellar of a barn rather than outside where some nutritional value of the manure could be washed away by rain. Since the Great Stone Barn was built into sloping rock ledge, the barn could not have a full cellar. With this challenge, the North Family Shakers located their manure cellar – or “manure vault” as they referred to it to emphasize the value of its contents – at the downhill end of the barn where they could have a full one-story storage space. Cows were stabled along both sides of the barn with their heads facing a center walkway from which the brothers tended them. Manure was, therefore, deposited along the full length of both sides of the barn and transported to the end of the barn to be dropped into the manure vault one story below. To ease the task of collecting and transporting the heavy manure, the Shakers installed a railroad track on the wooden floor along the length of both sides of the barn. The track exited the stable floor and continued along a semicircular platform over the manure vault and returned to run the entire length of the stable floor on the opposite side of the barn. Above the vault, a section of rails connected to the semi-circular track by two turntables that ran straight from one side of the barn to the other in order to more evenly distribute manure. On this system of rails, the Shakers had one or more low four-wheeled cars that were filled with manure, pushed along the railroad over the vault, and emptied into the accumulating pile below. The “manure railroad” was in use in the barn from its completion in 1860 until 1901 when the Shakers replaced decaying wooden floors under the cow stables with an expanded steel floor covered with Portland cement. At this time the handling of manure was done with some version of a manure carrier that ran on an overhead track.

Railroad Turntables, Great Stone Barn, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1950s. Photographer unidentified.

Manure from the vault was often mixed with nutrient-rich muck dug from a nearby swamp and other compostable materials. It was removed from the vault by hand-loading it into ox carts and transporting it to be spread in nearby fields. It was recorded that on the last few days of 1882, 56 ox loads of “manure from the cow barn vault [was spread] up on the potato field.”

No examples of the use of a rail system for manure handling in barns have been found outside the North Family’s barn. Elder Frederick W. Evans, the North Family elder responsible for building the Great Stone Barn, most likely recalled the use of small-scale railroads and cars from his boyhood-days of living in Worcestershire, England, where coal was mined using a similar method to transport coal from coal pits, and applied it to the barn.

Terrific story Shaker ingenuity.