Granary with Black Locust Tree, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1930, Historic American Buildings Survey, General View, of Shaker North Family. William F. Winter, photographer. Retrieved from: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny0537.photos.115512p/

In New Hampshire they say locust posts last about one year shy of granite ones. The same appears to be true in Columbia County, New York as well. On a walk around Shaker Museum’s historic North Family property in New Lebanon, one notices an abundance of old black locust trees. Their deeply furrowed bark and […]

In New Hampshire they say locust posts last about one year shy of granite ones. The same appears to be true in Columbia County, New York as well. On a walk around Shaker Museum’s historic North Family property in New Lebanon, one notices an abundance of old black locust trees. Their deeply furrowed bark and the way their trunks seem to emerge from the ground as a solid straight cylinder make them a dramatic addition to the landscape. The black locust, robina pseudoacacia, for those with a scientific bent, is native to North America – thought to have originated in the Appalachian Mountains as well as on the Ozark Plateau of Missouri and Arkansas. At present, black locust can be found in all the lower 48 states. First identified by British settlers in Jamestown in 1607, where it was used for the construction of dwellings, it was exported to England in 1636 and has since been cultivated around the world. In addition to being useful as a timber tree, black locust is excellent firewood, having the highest heat content of any tree in the Eastern United States, one approaching that of anthracite coal. Black locust flowers are also a favorite of honey bees. However, it is a fourth characteristic of the tree that explains the large number growing at the historic Mount Lebanon site: the heartwood contains chemical compounds that make the wood exceptionally resistant to rotting – even buried in the ground. It is therefore a preferred wood for fence posts, either as natural round tree trunks, split into halves or quarters, or a sawn square. It was this characteristic, and apparently use, that caused the Shakers, specifically Elder Richard Bushnell, to begin the propagation of black locust at the North Family.

Granary with Black Locust Tree, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1930, Historic American Buildings Survey, General View, of Shaker North Family. William F. Winter, photographer. Retrieved from: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny0537.photos.115512p/

On June 14, 1914, an unsigned article in the Chatham Courier newspaper titled, “Mount Lebanon,” provides a starting place for the story of the North Family locust trees. The article was probably written by Sister Leila Taylor (1854-1923) as she was a frequent contributor to the Chatham Courier — providing the paper with news about what was happening at the Mount Lebanon Shaker Village. The article begins: “The world of Lebanon, hill and valley, has been a wonderland of white bloom and a very Mount Hymettus to the bees. Never have the locust blooms been so abundant and beautiful. The groves planted by Robert White and Elder Richard Bushnell have multiplied until the whole countryside is a June fairyland.” The planting of these “groves” were described in 1850 in a late-September/early-October entry in the North Family Book of Records: “Elder Richard plants out about 1200 Locust trees in the lot below the small orchard west of the garden.” This is the first mention of locust trees that has, to date, been discovered in any North Family journal. It is likely that the Church Family had started a locust grove for fence posts a bit earlier. Their member, Brother Nicholas Bennet, according to the Ministry Journal kept by Elder Rufus Bishop, on April 29, 1848, “returned from W.Vliet where he had been after Locust trees.”

Whether the idea of creating a locust grove was Elder Richard’s or that of Robert White is not known. White was a Quaker whose spiritual journey led him to join the Shakers at Hancock, Massachusetts, however, because his wife failed to share his fervor, he became a frequent visitor to the Shakers – usually at the North Family – rather than a fully united member of the Church. A week or so prior to Elder Richard Bushnell planting locust trees, it was noted that Brother “Andrew Firky meet Robert White to the Depot.” It was also noted that Robert White left to return to his home in New York on October 1st. The mention of White in the Chatham Courier article suggests that this may have been the time that Elder Richard and Robert White created the first North Family locust grove. Although there is no mention of the harvesting of locust trees for posts until June, 1875, when the North Family cut 4000 locust posts, there must have been earlier sales. Locust grow large enough to make fence posts faster than many other trees – a black locust will grow to a height of 25 feet or more in its first three years. In addition to the frequent harvesting of locust posts between 1875 and the late 1880s, the parts of the locusts that were not useable for posts were cut up by the brothers for firewood.

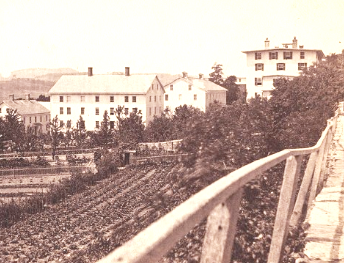

Stereograph, “Shaker Village, Mt. Lebanon,” ca. 1870s, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 2019.19.1. James Irving, photographer. This view from the south shows the North Family’s vegetable garden under cultivation.

The speed with which locust grow, coupled with their ability to reproduce both by self-seeding and by sending up new saplings from their roots, has caused them to be considered an invasive species in many places. The locust trees at the North Family that are now reaching the end of their expected 80 to 100 year life-span are undoubtedly self-propagated. There are a large number of mature trees growing in what was until the late 1930s the North Family vegetable garden. It is doubtful that the Shakers intended that area to become a black locust forest. For the past few years as these mature locusts have given up, lost their footing in the ground, and blown over in wind storms, the staff and students at Darrow School have been able to cut them up and make use of the excellent firewood to fuel their maple syrup production.

The North Family Vegetable Garden as It Appears Today with Mature Black Locust Trees, 2020. Staff photograph.