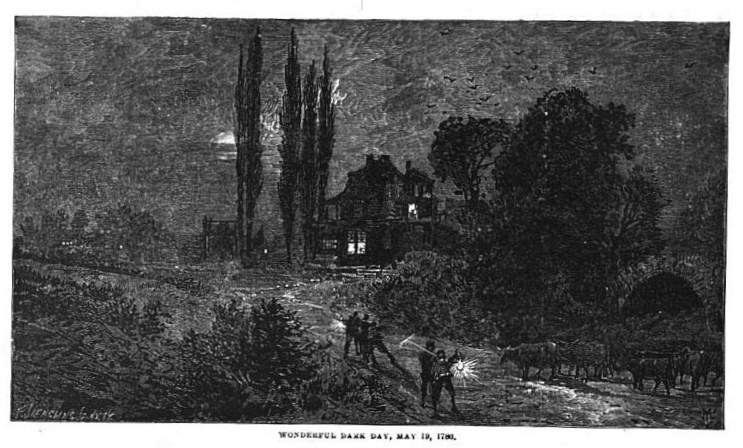

On May 19, 1780, the skies over New England and New York darkened for a full day. In the preceding days, the sun and moon had appeared red-tinted, and by noon of May 19, the sky was nearly dark as night. It was known as “The Dark Day.” One contemporary observer wrote, “The extent of […]

On May 19, 1780, the skies over New England and New York darkened for a full day. In the preceding days, the sun and moon had appeared red-tinted, and by noon of May 19, the sky was nearly dark as night. It was known as “The Dark Day.”

One contemporary observer wrote, “The extent of this darkness was very remarkable…. Candles were lighted up in the houses; the birds having sung their evening songs, disappeared, and became silent; the fowls retired to roost; the cocks were crowing all around as at break of day; objects could not be distinguished but at a very little distance; and everything bore the appearance and gloom of night.”

The phenomenon was also commemorated by poet John Greenleaf Whittier, who wrote in his 1866 poem “Abraham Davenport”:

‘Twas on a May-day of the far old year

Seventeen hundred eighty, that there fell

Over the bloom and sweet life of the Spring,

Over the fresh earth and the heaven of noon,

A horror of great darkness, like the night

In day of which the Norland sagas tell,–

The Twilight of the Gods. The low-hung sky

Was black with ominous clouds, save where its rim

Was fringed with a dull glow, like that which climbs

The crater’s sides from the red hell below.

Birds ceased to sing, and all the barn-yard fowls

Roosted; the cattle at the pasture bars

Lowed, and looked homeward; bats on leathern wings

Flitted abroad; the sounds of labor died….

Modern dendrochronological studies have confirmed that the cause of the Dark Day was smoke from massive forest fires in Canada pushed south by wind currents, combined with cloud cover and foggy conditions.

Some of those who observed the phenomenon believed it indicated that the end of times, or Judgment Day, had come. Elder Issachar Bates, one of the first and most successful Shaker missionaries, wrote an account of the event in his Sketch of the Life and Experience of Issacher Bates:

Soon after my return home from West Point my mind was again troubled with the phenomenon of… the ‘Dark Day’ all over New England. This baffled all human skill, for it was given up by great and small, that there were neither clouds [nor] smoke in the atmosphere, yet the sun did not appear all that day – and that day was as dark as night. No work could be done in any house without a candle! And the night following was as dark accordingly altho’ there was a full grown moon. I was going to a neighbor’s house in company with a young man, and as we passed several houses the people were out wringing their hands and howling ‘the day of judgement is come’!! This made the young man look pale – I made as light of it as I could, but it felt awful.

The Dark Day arguably set into motion the actions and events that transformed the Shakers from a small group of Believers into what became a society that included thousands of individuals living in nearly 20 communal villages. Indeed, according to Elder Calvin Green’s biography of Father Joseph Meacham, “The first public testimony of the gospel in America was delivered by Father James [Whittaker] at Watervliet on the well known dark day.” On that day or soon after, Mother Ann Lee and Father James commenced public preaching, and a number of converts who became life-long Shakers, such as Hannah Goodrich, visited Mother Ann at Watervliet in June; so it might also be argued that Mother Ann found a way to transform a distressing experience into a positive outcome, as many of us may feel called upon to do today.

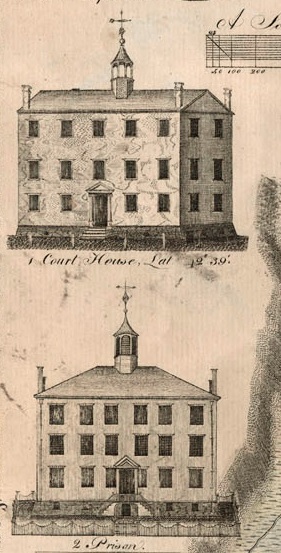

Within weeks, the Shakers also drew the notice of the authorities they had until then avoided. Mother Ann and the first followers, who engaged in ecstatic expressions of worship that were seen by many as odd or even threatening, were also British citizens regarded with suspicion by the American colonists. But it was not until after the Dark Day, on July 7, that the Shakers ran afoul of the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies. The committee, established in 1778, had broad authority to arrest and imprison suspected British spies and sympathizers. On July 7, 1780, Brother David Darrow and two others were arrested for bringing sheep from New Lebanon to Niskeyuna, on the grounds that “there is the greatest reason to suppose from their disaffection to the American Cause that they mean to convey [the sheep] to the Enemy.” The Shakers, instead of disavowing the principle of pacifism for their own safety, testified to the committee that, “it was their determined Resolution never to take up arms and to dissuade others from doing the same.” The Committee declared that “such principles at the present day are highly pernicious and of destructive tendency to the Freedom & Independence of the United States of America,” and committed Darrow, Joseph Meacham, and English convert John Hocknell to jail.

Later that month, the Committee ordered the apprehension of the Shaker leaders:

Frequent complaints have been made by sundry of the well affected inhabitants of this County that John [Partington], William [Lee], and Ann Standerren [Lee], by their conduct and conversation disturb the publick peace and are daily dissuading the friends to the American cause from taking up Arms in defense of their Liberties.

These three, like the others, did not deny that they had “endeavored to influence other persons against taking up arms,” so in August, they were remanded to the prison in Albany.

Detail from engraving, “A Plan of the City of Albany, 1794,” showing the Albany Court House and Prison. Collection of the Albany Institute of History and Art.

Yet Mother Ann again created opportunity from adversity; according to Shaker tradition, she spoke through the window of the jail to followers who’d gathered outside, and perhaps attained a greater level of renown. In May of 1781, about a year after the Dark Day, building upon a scattered but growing population of converts, Mother Ann and the leaders embarked upon a two-year missionary expedition through New England which led to the founding of several Shaker communities.

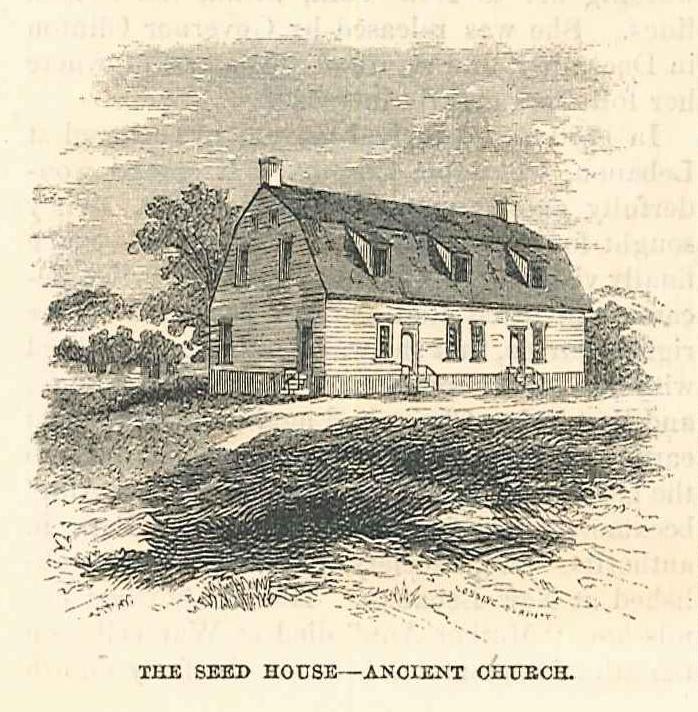

Mother Ann died not long after returning to Albany in 1784, having endured frequent abuse and hardship. But her work was continued by her successors Father James Whittaker and, in particular, Father Joseph Meacham. In August 1788, the first communal dwelling was raised at Mount Lebanon, under Meacham’s direction. The first meetinghouse at Mount Lebanon was built in 1785 and the course was set for a way of life that endured at Mount Lebanon for more than 150 years.

The first meetinghouse at Mount Lebanon. Engraving published in Harper’s Monthly, 1857.

Well done.

Thanks for reading Tom.

Fascinating! What courage of their convictions these Shakers had , setting us a good example in this trying time.

Excellent and very interesting history and a wonderful lesson in courage and determination.