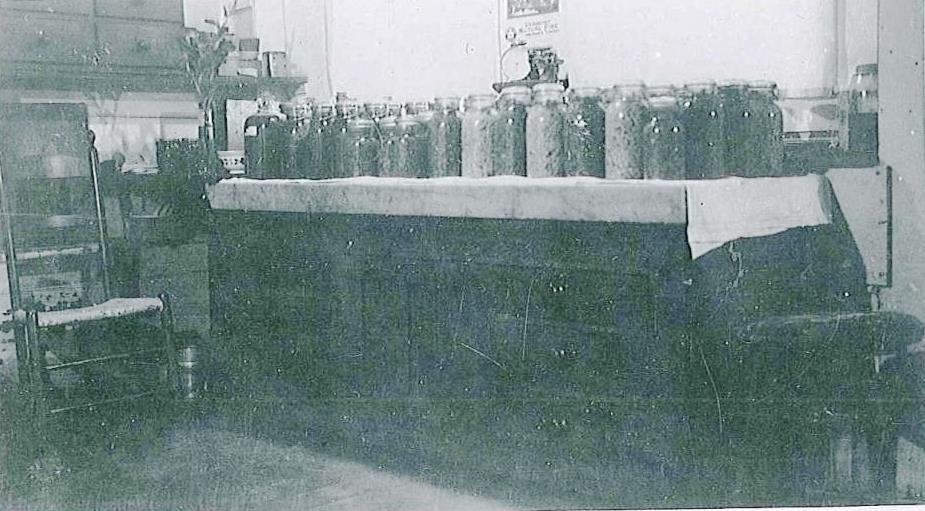

Counter, Church Family, Canterbury, NH, 1850-1900, Shaker Museum: 1961.13182.1. John Mulligan, Photographer.

When this counter was acquired from the Canterbury Shakers in the fall of 1961, the Shakers informed the Museum’s director that it had been used in an area where canning and candy-making were done – most likely in the family’s Syrup Shop. The Canterbury Shakers, according to Eldress Bertha Lindsay and Sister Lillian Phelps, in […]

Counter, Church Family, Canterbury, NH, 1850-1900, Shaker Museum: 1961.13182.1. John Mulligan, Photographer.

When this counter was acquired from the Canterbury Shakers in the fall of 1961, the Shakers informed the Museum’s director that it had been used in an area where canning and candy-making were done – most likely in the family’s Syrup Shop. The Canterbury Shakers, according to Eldress Bertha Lindsay and Sister Lillian Phelps, in Industries and Inventions of The Shakers … A Brief History, “had an orchard of over 1,000 maples, situated about a mile northeast of the village. Maple products such as syrup, maple sugar cakes, pulled candy [i.e. Taffy] and clay sugar formed a thriving industry for many years.” When Elder Giles B. Avery visited Canterbury in 1843 on a trip to direct the printing of The Holy Roll and Book, he noted that he was taken to visit the sugar camp from which the Shakers had made about 2,000 pounds of sugar the previous season. He learned that, though profitable, it was more so for them to make clarified maple molasses than sugar. It was apparently this maple molasses that most often found its way to the top of this counter. The heavy marble top would take a lot longer to heat up than the rest of the room. When hot thick maple syrup was dropped on the cold surface of the marble, it made small maple-flavored candy drops – one of the products sold in the Shakers’ store. During canning season, the marble top made a convenient surface upon which to let recently filled canning jars cool. A photograph of the counter taken by Eldress Bertha Lindsay as part of her photographic documentation of life at Canterbury shows the counter being used for this purpose.

Photograph of Counter in the Syrup Shop, Church Family, Canterbury, NH. Shaker Museum: 1964.6755.61. Eldress Bertha Lindsay, Photographer.

The counter itself was clearly purpose-built to hold the heavy marble top. The slab of marble – 3 1/2 x 75 7/8 x 24 3/8 inches – weighs an estimated 600 pounds. The counter is constructed much like a carpenter’s workbench, with heavy posts for legs and nearly equally heavy beams supporting the top. These are joined by mortise and tenon joints that have had iron bolts run through them to make sure that they would not come loose under the weight of the top. One curious feature of the piece is a system used to lock all six drawers. From the lockable cupboard, holes in the sides of cupboard are aligned with holes in the sides of the drawers. Rods can be inserted through the sides of the cupboard through the sides of the drawers. Once inserted and the cupboard door locked, there is no access to the any part of the insides of the counter.

Unfinished Edge of Marble Top of Counter, Church Family, Canterbury, NH. Shaker Museum: 1961.13182.1. John Mulligan, Photographer.

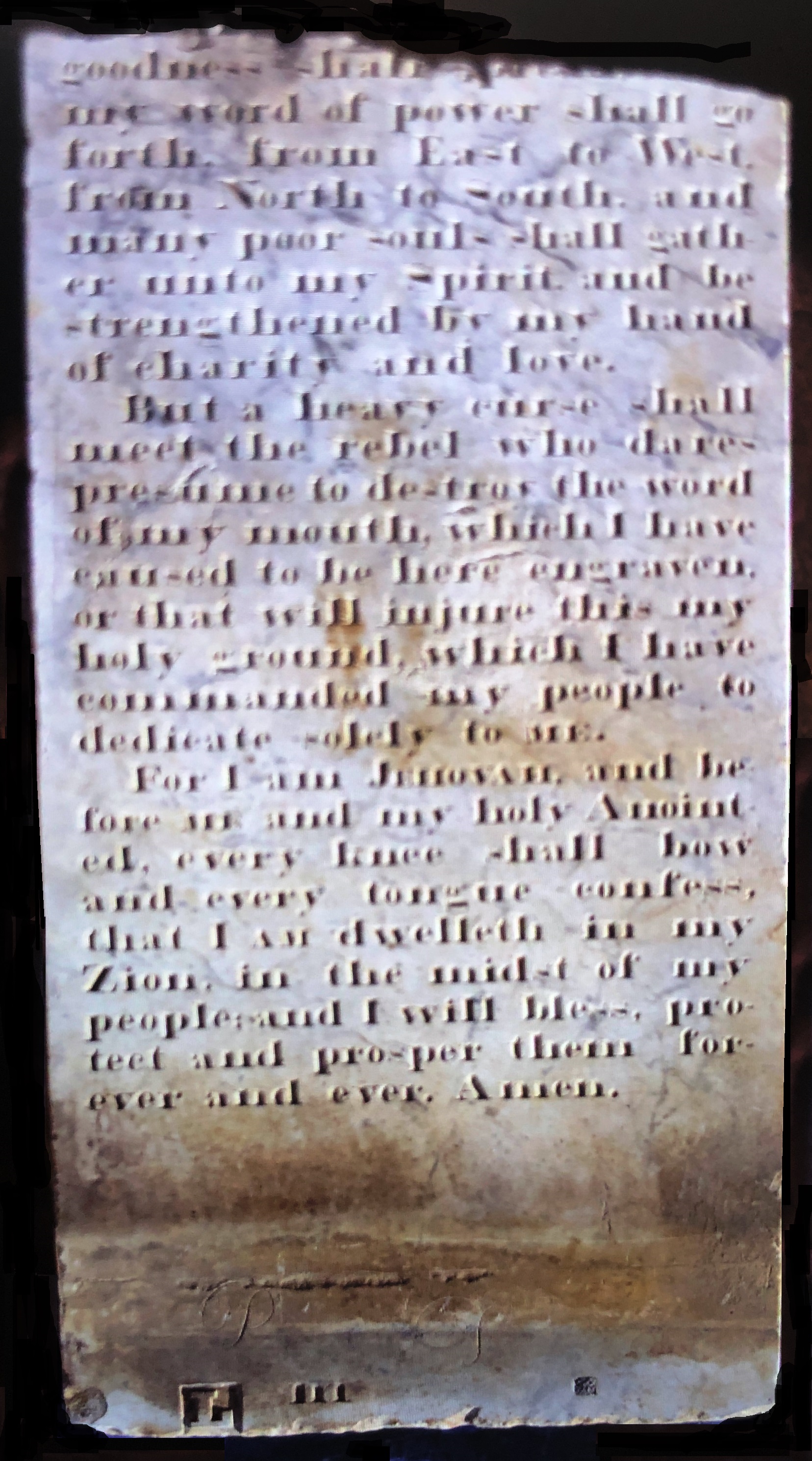

Beyond this feature, the marble top provides a possible mystery yet to be solved. During the Shakers’ Era of Manifestations each Shaker community selected a piece of their land to be designated as a holy feast ground, upon which they would hold outdoor worship. At Canterbury, this piece of land, called Pleasant Grove, was selected in October, 1842. The area was cleared and enclosed with a fence. A small building – a shelter for worshipers during bad weather – was constructed. To complete the feast ground the Canterbury Shakers were expected to set aside a special area – a spiritual fountain – at its center. At the head of the fountain they were to erect a stone with a text, delivered by an angelic spirit, carved into it. At Canterbury, this final step was not completed for several years, until the fountain stone was erected on June 24, 1848. The stone had been purchased in March 1847. Elder Joseph Myrick of Harvard, came to Canterbury to begin the lettering and to train a young brother, Henry Clay Blinn, to complete the work. That stone, described by Eldress Emma B. King, as a piece of “beautiful Italian marble,” was given to the Shaker Museum by the Canterbury Shakers in September, 1953. The stone had been taken down around 1860 and stored away. It had been broken – probably by vandals – which could have created some urgency in removing it, although by that date, the Era of Manifestations had pretty much run its course. Somewhere between three-fifth and four-fifths of the stone remain. The dimensions of the remaining marble section are: 4 x 541/4 x 27 1/4 inches. Given the estimates of how much of the stone remains, it appears that the original stone may have been around 75 inches long. One end of the marble counter top was not finished in the careful manner as were the other three edges, suggesting that the stone cutter may have expected that end of the stone to be buried in the ground. The size of the counter’s stone in comparison to the fountain stone and the possibility that it was probably not made specifically for the counter – or all the sides would have been similarly finished – but rather was likely some surplus piece the Shakers had on hand – opens the possibility that the stone on the counter was an unfinished blank that for some reason had been rejected for a fountain stone.

Fountain Stone, Church Family, Canterbury, NH, 1847, Shaker Museum: 1953.6619.1. Michael Fredericks, Photographer.

In the collection of Hancock Shaker Village there is a stone acquired at Mount Lebanon that closely matches the fountain stone that was lettered at Mount Lebanon for the Groveland Shaker community. When Hancock acquired it, it was unlettered, and in the late 1970s and early 1980s a local stone cutter lettered the stone with the inscription that had appeared on the Hancock fountain stone that no longer existed. At the Enfield community in Connecticut, the Shakers went to Lanesboro, Massachusetts in May, 1843, to purchase a new fountain stone blank – their first stone having failed because it was too “flinty.” These two examples demonstrate that there were unfinished or incomplete blanks for fountain stones beyond those that were eventually erected on feast grounds.

Whether this mystery is ever solved, it is interesting to think that had the Canterbury Shakers had a second blank for a fountain stone – whether found to be unusable or purchased in case something happened to the first one – that they, in their very practical way, repurposed as a counter for making candy.

Wonderful insight(s) here, the result of clear and careful thought. Thank you!