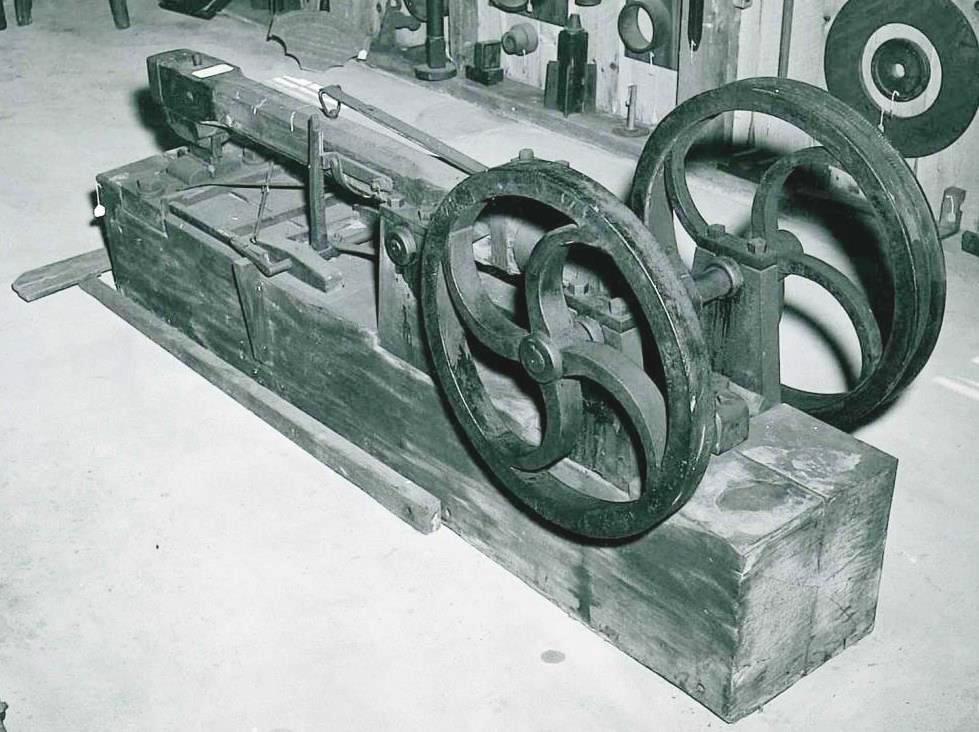

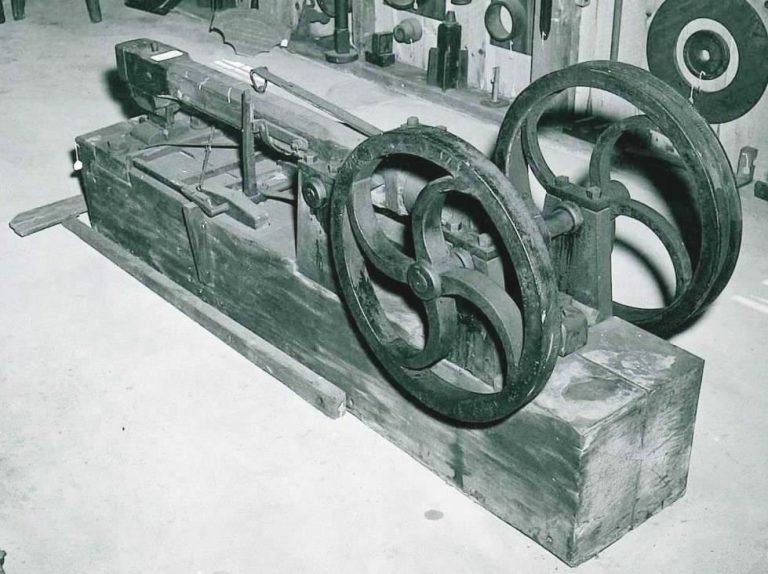

Trip Hammer, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, c1955, Shaker Museum Institutional Archives showing the trip hammer on exhibition.

In 2016 the Museum published a blog post about a trip hammer built by the Church Family Shakers in 1847 to be used in their new blacksmiths’ workshop. The new trip hammer was an industrial size machine with the capability to shape hot metal of any size the Shaker might need forged. Trip hammers of […]

In 2016 the Museum published a blog post about a trip hammer built by the Church Family Shakers in 1847 to be used in their new blacksmiths’ workshop. The new trip hammer was an industrial size machine with the capability to shape hot metal of any size the Shaker might need forged. Trip hammers of many designs and for many uses have been around for a couple of thousand years. They were invented and reinvented to crush grain into flour, pound rags into pulp for paper, crush metal-bearing rock prior to smelting, and for shaping iron that was difficult to shape with only the power of the smithy’s arm. Trip hammers require a power source, usually waterpower, but they could be supplied by animal power. The Shakers, in preparation for their new trip hammer, even experimented, apparently unsuccessfully, with wind power – as it is recorded on January 5, 1846 that, “Elder Brother has been making a model for a windmill in hopes to tilt a Triphammer.” Whatever the power source, the principle of the trip hammer was to use some sort of power to raise the heavy head of the hammer above the anvil mounted in the base of the trip hammer. Once raised, the hammer was held in position by a spring-loaded support until the blacksmith, with the hot iron properly positioned on the anvil, “tripped” the hammer with a foot lever to let it drop onto the iron. The blacksmith could, if appropriate, hold the foot lever down to make the hammer continuously move up and down – pounding on every down stroke.

Trip Hammer, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, c1955, Shaker Museum Institutional Archives showing the trip hammer on exhibition.

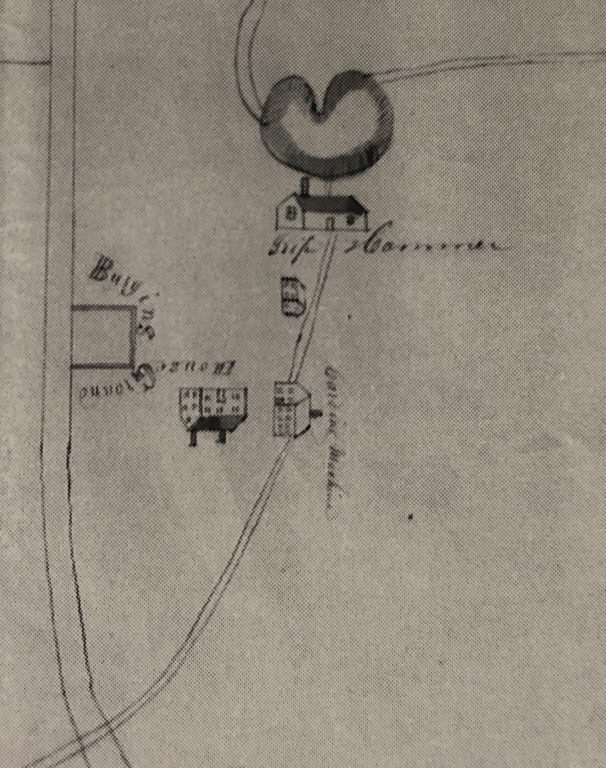

The Shakers at Mount Lebanon had built trip hammers prior to the massive one built in 1847. Brother Isaac Newton Youngs, a nearly life-long member of the Church Family at Mount Lebanon, wrote a manuscript history of that family titled, Concise History of the Church of Christ on Earth in 1856. In it he notes that in 1800 the family had made “valuable improvements” in the blacksmithing trade including “erecting a trip hammer for drawing of heavy irons,” although he commented that it was “of an indifferent construction.” The trip hammer also required the building of a dam and waterwheel to supply power to lift the hammer. A map, drawn by Brother Isaac sometime between 1827 and 1839, shows the location of a trip hammer and the pond that supplied its power. It was located in a small group of buildings located off what is now called Ann Lee Lane just to the south of the Church Family burying ground. The building are labeled as “House,” that is a dwelling house, “Carding Machine,” at which the community carded their wool prior to spinning, and “Trip Hammer.” The buildings are long gone and their location is now private property.

Map Drawn by Brother Isaac Newton Youngs (detail), ca.1827-1839. Private Collection, Reproduced from Shaker Village Views, by Robert P. Emlen [Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1987].

To consider the object at hand – a trip hammer in the collection of the Shaker Museum that was acquired at Mount Lebanon’s North Family – there is yet another trip hammer encased in somewhat of a mystery as to its origin. Is there a chance that it is a trip hammer of less “indifferent construction” used by Elder Daniel Boler to pound ash logs? There is no mention of a trip hammer in the known records of the North Family prior to April 1, 1864, when the North Family Shakers, “Put up walls on the West side Brick Shop [to support the badly failing west wall]; two abutments of stone containing 200 perch: Brick walls upon these to the Eaves. Also a Blacksmith Shop is added for a trip hammer.” The fact that there is no previous mention of a trip hammer in the family and the noting that there was a room for “a trip hammer,” rather than “our trip hammer,” gives one pause to consider that the trip hammer was new to the family. The trip hammer used in this workshop was powered by a series of line-shafts, pulleys, and leather belts connected to a waterwheel in the Brick Shop. Sometime in the late 1870s the trip hammer was moved to a building a dozen yards west built in 1849 as a Wood House to supply firewood for the Brick Shop and the family laundry located within it. However, as the need for firewood was considerably reduced when the family laundry was moved to a building closer to their dwelling houses, the south end of the building was set up as a blacksmiths’ shop. A line-shaft was run from the Brick Shop into the Wood House to power both the trip hammer and the bellows for the forge.

Hammer End of Trip Hammer as it Appeared when Used at the North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Historic American Buildings Survey: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/pnp/habshaer/ny/ny0500/ny0541/photos/115500pv.jpg William F. Winter, Photographer.

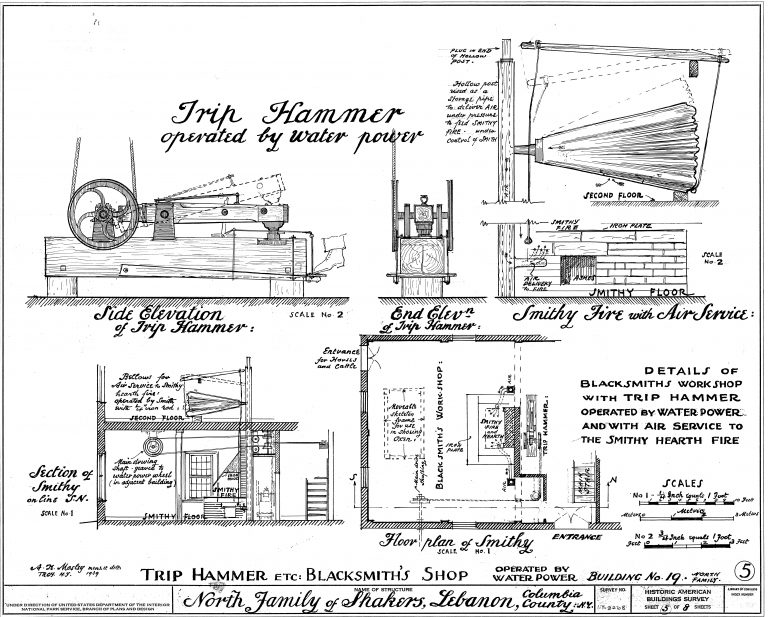

In the late-1920s, William F. Winter, working as a photographer for the New York State Museum to record the architecture and material culture of the Shakers at Mount Lebanon, Hancock, and Watervliet, made a photograph that captured the North Family’s trip hammer in its location directly behind the Forge – easily accessible to the blacksmiths. In 1939, after Winter’s photographs had become part of the Historic American Buildings Survey, that project sent delineator A. K. Mosley to draw many of the Shakers buildings, including the Forge at the North Family. Mosley left a sketch of both the trip hammer and the way it was connected to the power source coming from the Brick Shop. With Winter’s photograph and Mosley’s drawings we have excellent documentation of where and how the Museum smaller trip hammer was last used by the North Family Shakers.

Drawing of the Interior of the Forge, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1927. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Historic American Buildings Survey: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny0541.sheet.00001a/resource/

The note illuminateda great deal to me about Shaker daily life.

The note illuminated a great deal to me about Shaker daily life.