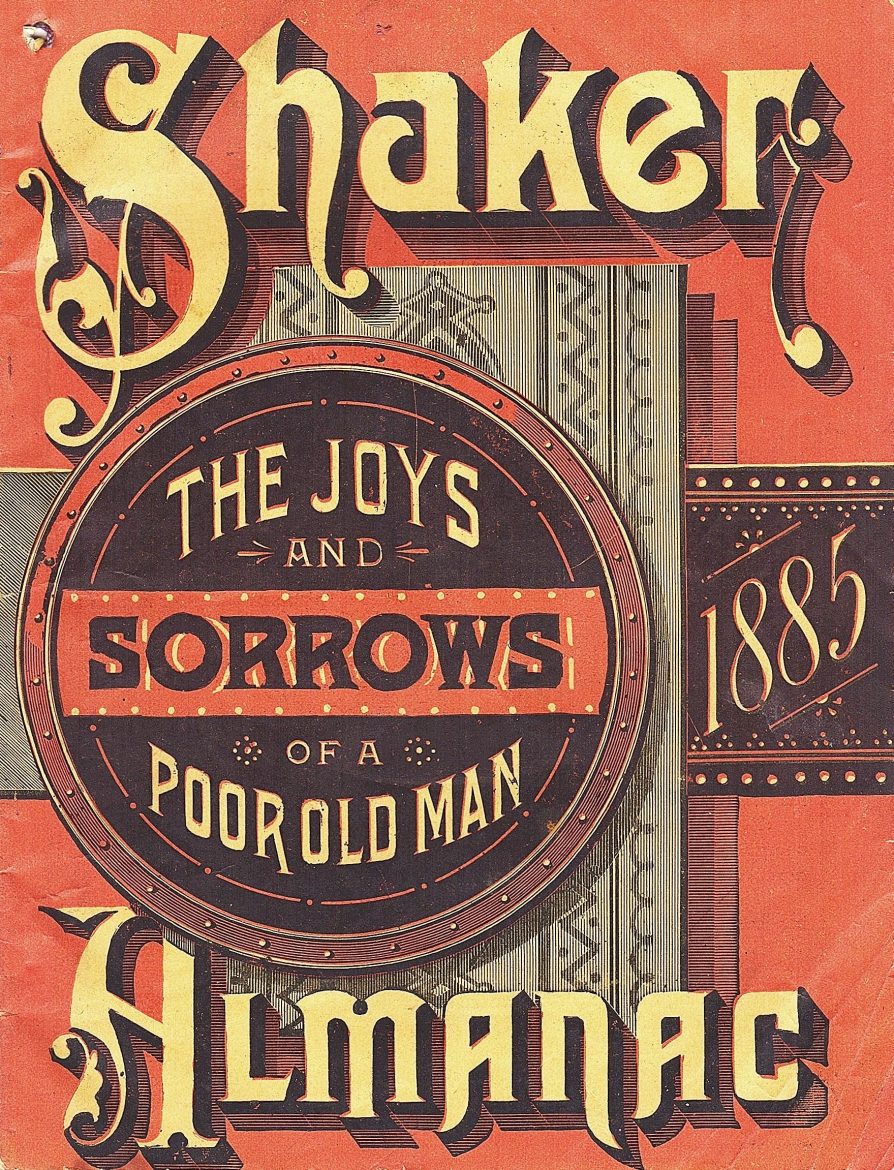

Shaker Almanac: The Joys and Sorrows of a Poor Old Man, 1885. [New York: A. J. White, 1884], Shaker Museum: 1984.19-75.1.

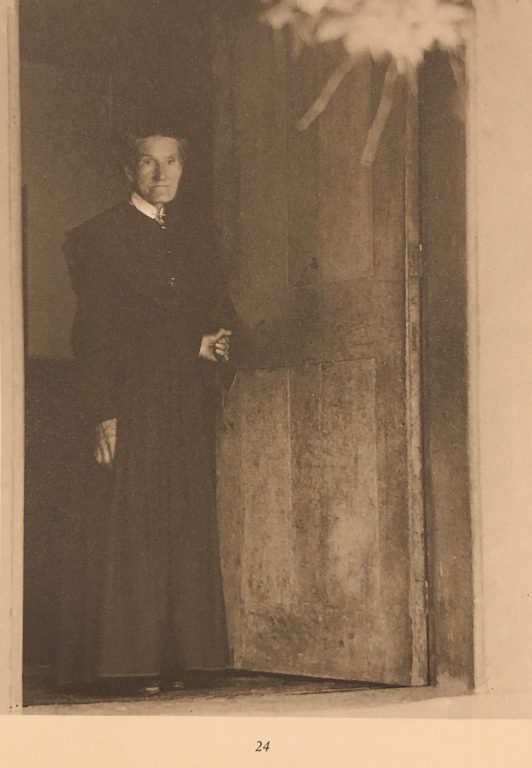

A half-dozen years ago a Shaker Museum blog post explored the work of New York photographer Doris Ulmann (1882-1934) that resulted in portraits of Shaker brothers and sisters from the Second and South Families at Mount Lebanon. Her work, an exploration of American “types” – Appalachian mountaineers, Mennonites, Gullah Islanders, and Shakers, appeared in several […]

A half-dozen years ago a Shaker Museum blog post explored the work of New York photographer Doris Ulmann (1882-1934) that resulted in portraits of Shaker brothers and sisters from the Second and South Families at Mount Lebanon. Her work, an exploration of American “types” – Appalachian mountaineers, Mennonites, Gullah Islanders, and Shakers, appeared in several exhibitions and publications during her lifetime, and more after her death.

The Appalachian Photographs of Doris Ulmann, with an introduction by John Jacob Niles [Highlands, NC: The Jargon Society, 1971], plate 24.

The French Maid, c. 1900, Underwood & Underwood Studio, New York, NY. Copy photograph of original in a private collection.

The inclusion of Sister Sarah in Appalachian Photographs appears to be a mistake due to a lack of documentation left by Ulmann, whereas a stereograph showing a provocatively posed woman in a Victorian parlor, includes a Shaker rocking chair – probably a No. 6 or 7 armless rocker – purely by happenstance. The other rocking chair in the view – the one with the spindled-back – is a Shaker-style chair manufactured by a non-Shaker company, likely the Enterprise Chair Works of Union City, Pennsylvania. The stereograph was probably produced in 1900 by the photographic studio, Underwood & Underwood, as part of a ten-view “risqué” series titled “The French Maid.” Underwood & Underwood, although founded in Ottawa, Kansas in 1881, moved their main office to New York City by 1887, where they became, at one time, the foremost producer of stereographs, producing as many as ten million cards a year. The image seems to have been created in a private home rather than in a studio. The appearance of a Shaker rocking chair in that setting is truly surprising.

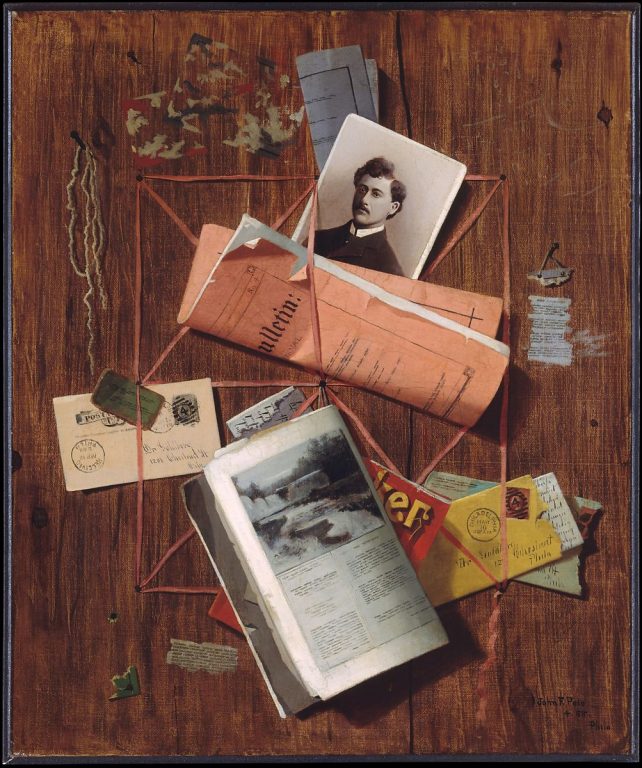

“Office Board,” by John Frederick Peto, 1885. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1955.176. Image retrieved May, 2022, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11761?ft=john+f+peto&offset=0&rpp=40&pos=3.

Unlike the two earlier examples, artists rarely include objects in their work without forethought. On a day spent at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a Shaker Museum staff member took note of a painting by John Frederick Peto (1854-1907) titled “Office Board.” The trompe-l’oeil painting depicts a collection of items held on a wall or bulletin board by a web or narrow ribbons. The objects include pieces of correspondence, a photograph, a periodical, a ticket, several remnants of items incompletely removed from the board, and, peeking out from behind and mostly obliterated by what appears to be a pamphlet, a red-covered publication with the letters “ker” apparently part of its title. A certain amount of familiarity with the unusual typography and a bit of further investigation identifies the publication as the spring edition of the 1885 Shaker Almanac titled, The Joys and Sorrows of a Poor Old Man, published by the A. J. White Company – in collaboration with the Mount Lebanon Shakers – to promote medicinal preparations manufactured by the Shakers for White’s company. Following the terrible fire at Mount Lebanon’s Church Family in 1875, Brother Benjamin Gates, looking for ways to help the family recover from its loss, entered into an agreement with Andrew Judson White, which did, in fact, greatly benefit the Shakers – and, of course, White. White provided the medical formula for the product, and the Shakers, with their efficient and well-disciplined work force, manufactured and packaged White’s medicine as Shaker Extract of Roots (known as Mother Seigel’s Syrup outside the United States). In 1882, White began issuing an annual almanac bearing the Shaker name and promoting his medicines. According to the Metropolitan Museum’s records, Peto, a native of Philadelphia, painted Office Board in 1885 making his intentional inclusion of the 1885 Shaker Almanac all the more likely. The piece was, according to the Met, likely painted for his neighbor, Dr. Bernard Goldberg, a Philadelphia chiropodist. One of the pieces of correspondence tucked in “the rack” is addressed to him and the photograph Peto included may be of him. With that in mind, the inclusion of a medical almanac, Shaker or not, may have been quite intentional.

Shaker Almanac: The Joys and Sorrows of a Poor Old Man, 1885. [New York: A. J. White, 1884], Shaker Museum: 1984.19-75.1.

The Shaker Extract of Roots or Mother Seigel’s Syrup was, between around 1880 and 1898, the most widely distributed (and very possibly the largest selling) medicine in the entire World! A.J. White had sales agents in some 76 countries, from Aden to Zanzibar.

Destitute at the time he partnered with the Shakers in 1775-6, he was an extremely wealthy man at the time of his death in 1898. He owned mansions in New York City and London and endowed a building at his alma mater, Yale University.